Predict Childhood Obesity Using RF, XGBoost and GLMM in R

Introduction

Childhood obesity, a global concern affecting millions, is linked to serious health complications, including asthma, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes. Early identification of children at risk for obesity is crucial for prevention and management. This study aims to develop and validate a predictive model using fecal microbial features of 3-month-old infants to classify their risk for rapid growth trajectory, a key indicator of obesity, during preschool years. By focusing on longitudinal BMI-z trajectories, rather than static indicators, this model may fill a critical gap in pediatric obesity prediction, offering a clinically relevant tool that leverages gut microbiome data to enhance early intervention strategies.

Data

Data source: The dataset is a subset of 1,943 infants from the CHILD cohort study, which includes participants from four Canadian centers (Vancouver, Edmonton, Manitoba, and Toronto) collected between 2008 and 2012. Mothers met criteria such as being over 18 years old, living within 50 km of a participating hospital, and planning to deliver at a designated center. Children with significant congenital abnormalities or circumstances hindering follow-up were excluded.

Outcomes: The target labels for prediction were categorized into high-risk and low-risk groups based on BMI-z trajectories reported by Reyna et al., with high-risk participants having an 85% or greater probability of following a rapid-growth trajectory.

Predictor: The dataset comprised 2,450 stool samples collected from 1,943 infants, sequenced by the SyMBIOTA and BC laboratories, with some samples sequenced by both labs for validation. The primary predictors were genus-level relative abundances from 16S rRNA gene sequencing of stool samples collected three months after birth.

Analysis

Feature extraction and transformation: Feature extraction involved collapsing OTU tables to the genus level with the R package outSummary, scaling features within each stool sample to sum to 1, and removing taxa present in less than 10% of samples. A log-ratio (CLR) transformation of the relative abundance data was then applied, improving classifier performance slightly by log-transforming each feature relative to the geometric mean of all features in the sample.

Missing data handling: Missing values in gut microbiota features were replaced with zero and removed observations with missing target outcome labels.

Batch effect correction: In our study, “batch effect” refers to variations due to different lab or technical factors across experiment batches, which can confound results. We identified this effect using principal component analysis (PCA) and applied the ComBat algorithm to correct for it, removing batch-specific variance while preserving the key grouping information.

Exploratory data analysis: Principal component analysis (PCA) visualized gut microbiota structure, and Euclidean distance based on central log-ratio (CLR) transformed abundances assessed diversity. Redundancy analysis (RDA) explored relationships between genera and the target variable, controlling for covariates, with significance tested via ANOVA and permutation tests. Beta-diversity differences were analyzed using Aitchison distance and dispersion tests, and non-parametric PERMANOVA assessed centroid differences between outcome groups, with a significance level of 0.05.

Machine learning models

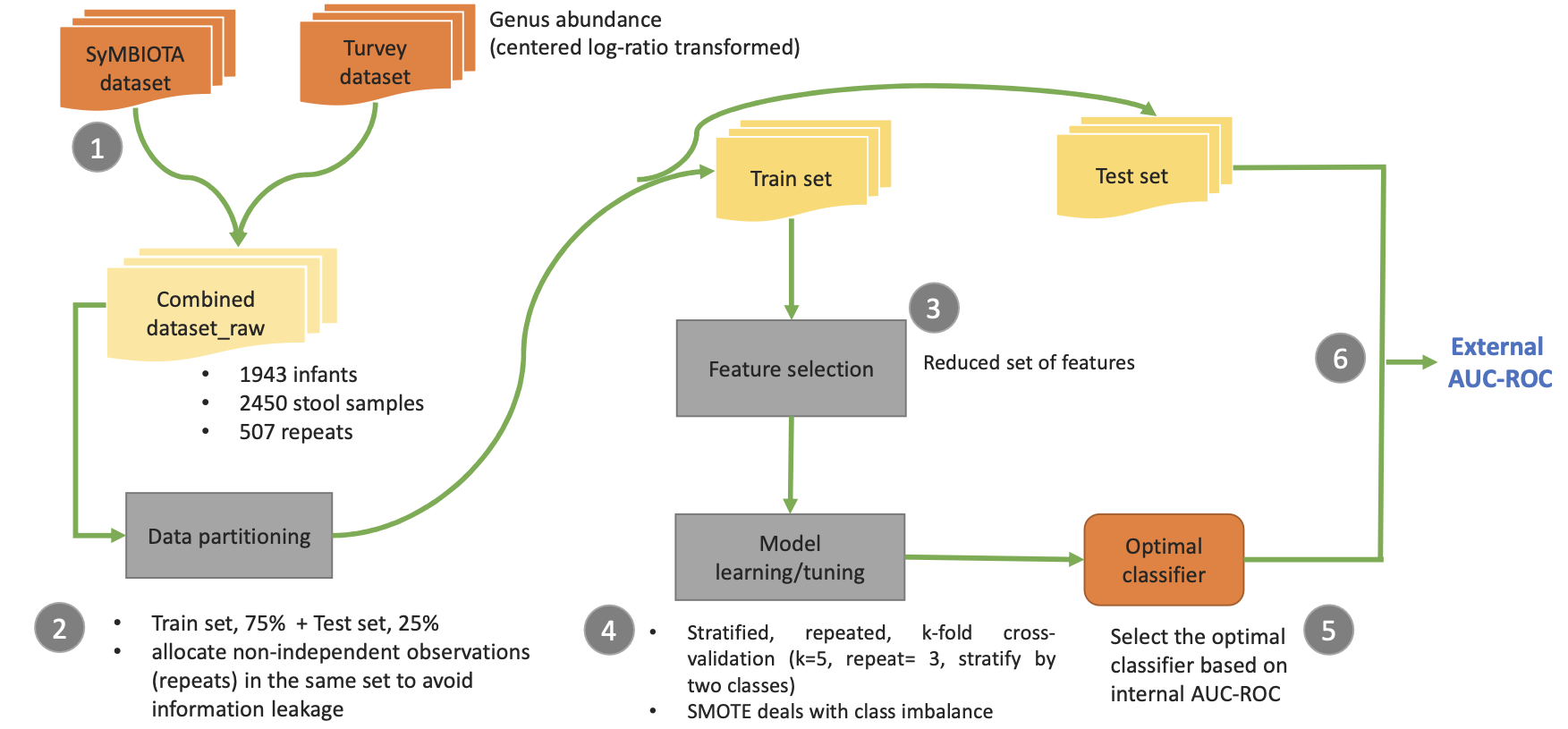

Design rational: We tested two approaches with data from two labs: (I) using the combined dataset with dummy laboratory covariates but no batch effect correction, and (II) applying batch effect correction using ComBat before training. Scheme I included non-independent observations in the same set during partitioning and used a generalized linear mixed model to handle random effects, while Scheme II removed batch variation to compare classifier performance.

Data Partitioning: In both schemes, non-independent observations (identical individuals) were kept together in the same subset, either training or test, with a 75%/25% split for the combined data. Unique observations were similarly split. Density plots confirmed non-independent observations did not skew the distributions of unique observations.

Data Transformation and Preprocessing: Microbiota data were normalized before preprocessing. We removed highly correlated features (Spearman coefficient >0.8) and features with near-zero variance using the R package caret to avoid issues with multicollinearity and instability.

Feature Selection: We selected features from the normalized training set using three methods: univariate statistical tests, AUROC-based permutation importance from Random Forest, and Boruta. Univariate tests proved to be comparably predictive, so we used them for feature selection. Recursive feature elimination (RFE) was then employed to determine the optimal number of features based on the chosen machine learning algorithms.

Model Training and Evaluation: To address imbalanced data, we used SMOTE during cross-validation to balance minority and majority classes and applied class weighting for multiclass classification. We employed stratified, repeated 5-fold cross-validation (3 repeats) for model training and tuning, using Random Forest, regularized logistic regression, XGBoost, GLM, and GLMM (via the R package lme4) to handle random effects. Model performance was assessed using CVAUROC (Cross-validation AUROC) to select the best classifiers.

Results

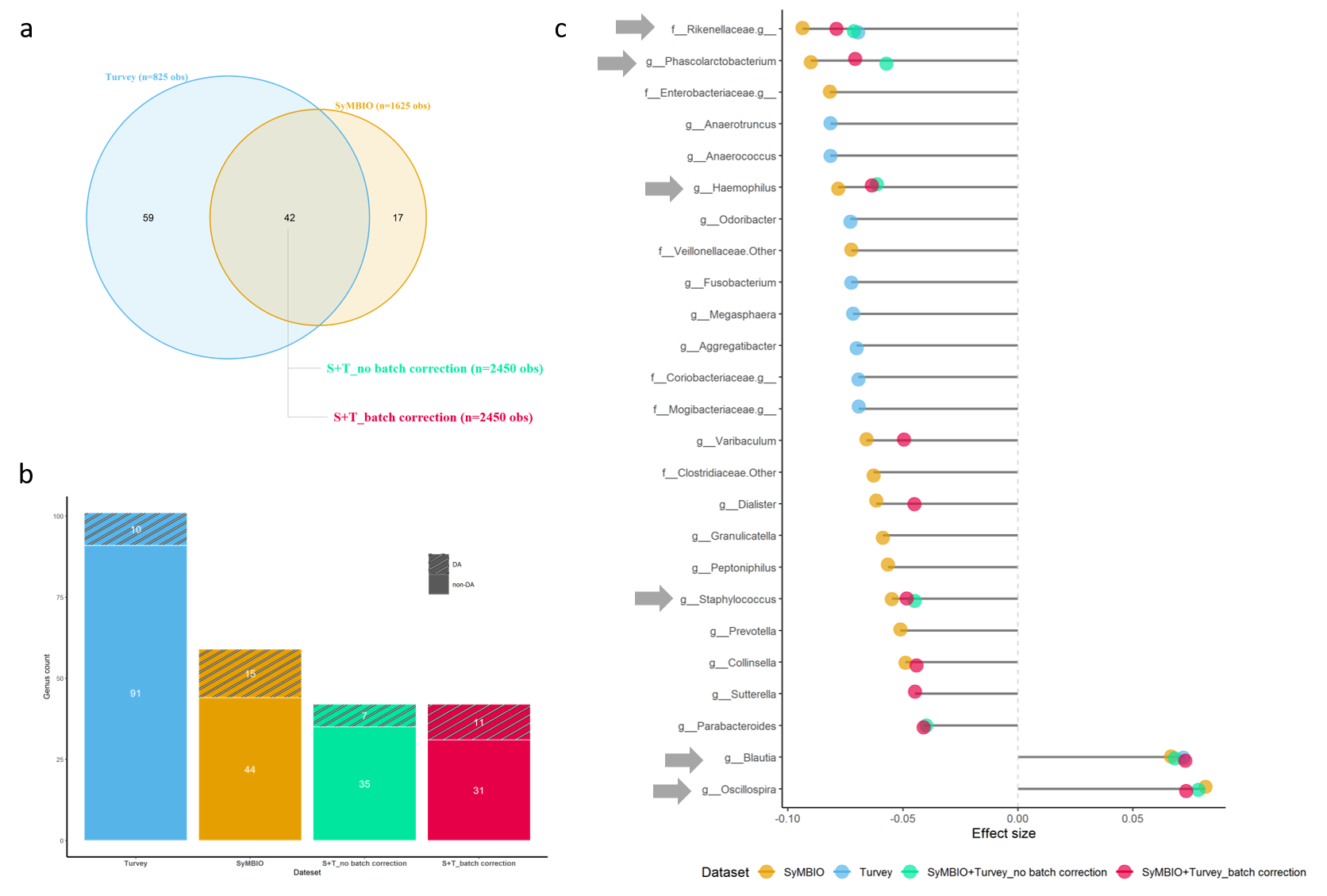

Exploratory data analysis: Batch effect removal improved detection of differentially abundant microbes, with the high-risk group (Traj4) showing distinct microbiota composition compared to others. High-risk microbes such as Blautia and Oscillospira were enriched, while genera like Haemophilus were less abundant. This group was notably different from low-risk groups, explaining a small but significant portion of gut microbiota variance.

Feature selection: We employed filter and wrapper methods for feature selection, both identifying similar key features. The filter method used univariate statistical analysis, while the wrapper method applied recursive feature elimination (RFE). RFE indicated that four predictors were sufficient for optimal predictive power, leading us to select five genera—Oscillospira, Rikenellaceae, Haemophilus, Blautia, and Phascolarctobacterium—for further model development.

Models: Among 36 machine learning classifiers tested, the GLMM model with microbial features and infant sex achieved the highest performance with an AUROC of 0.84. Batch correction did not notably enhance classifier performance, and statistical models like RegLog and GLM generally outperformed machine learning models like RF and XGBoost. The GLMM, accounting for repeat samples, improved predictive ability by 14-50% over non-mixed-effect models. Including infant sex in models improved performance, while lab and city variables had minimal impact.

Predictive features: Microbial features were the key predictors of the target variable, with a panel of five gut microbes—Oscillospira, Rikenellaceae, Haemophilus, Blautia, and Phascolarctobacterium—providing accurate predictions regardless of lab or province. Oscillospira and low Rikenellaceae were particularly predictive of the high-risk group. Covariables like lab, province, and sex had less impact on model performance compared to microbial features, with a GLMM model using only microbial predictors achieving similar performance to one that included infant sex.

Contributions

Project Implications:

- Fecal microbiome signatures are predictive of longitudinal obesity development.

- The GLMM-based model could aid clinicians in patient stratification and personalized interventions.

- Identifying a panel of four gut microbes may offer insights into obesity pathology.

Strengths:

- Addressed repeat measures bias by using GLMM with “infant” as a random effect, improving model performance.

- Mitigated imbalanced class issues with SMOTE during cross-validation, enhancing classifier accuracy.

- Lab-dependent microbiota variations did not impact predictive performance, indicating robustness.

Limitations:

- Potential limitations in handling extreme class imbalance might still affect some models.

- The impact of lab-specific protocols on microbiota composition, while controlled, could influence results in other settings.

Acknowledgments

- Dr. Anita Kozyrskyj supervised the study and advised on the proposed methodologies.

- Dr. Myrtha Reyna and Dr. Wendy Lou provided statistical counseling.

Appendix

The information of environment, R version and packages is here.